Mirror of the Body

February 8, 2011 § 5 Comments

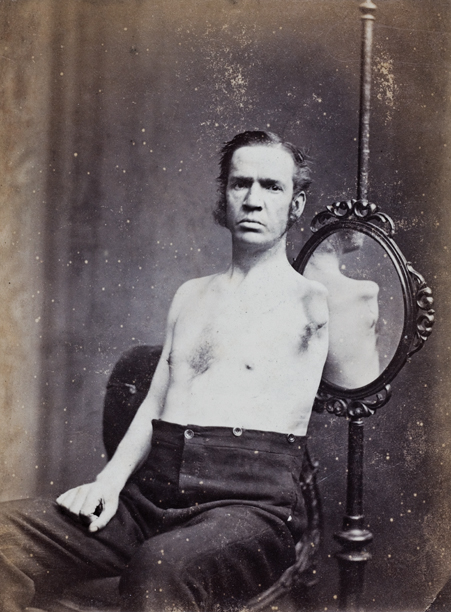

“Man with Shoulder Amputation, 1874, James Robinson, D.D.S., Dublin” © The Burns Archive. Used with kind permission.

Ever since seeing this fascinating photo of a man with a shoulder amputation on the cover of Scope Magazine, I have been interested in the use of mirrors in vintage clinical photographs. Using a mirror to reflect another view of a body part or wound was common in the mid-nineteenth century.

Looking for more photos with mirrors I contacted the Otis Historical Archives at the National Museum of Health & Medicine. They kindly went through their archive and posted all photos they could find with mirrors on their Flickr page. Most of these photos are from the American Civil War (1861-1865). It was both a time when a lot of clinical photos were taken, and a time with a large number of through-and-through gunshot wounds. Using a mirror, the photographer was able to capture both the entry and exit wound in one picture. Let’s take a look at some selected photos from the collection.

SP 093. “Penetrating Gunshot Wound of the Abdomen. General Henry Barnum, 12th New York. (CC-BY) National Museum of Health & Medicine.

This photo of General Barnum is an excellent example of this. Wounded on July 1, 1862 at the battle of Malvern Hill, Barnum was photographed for the Army Medical Museum three years later by photographer William H. Bell (1830-1910). Posed as a classic portrait, his left arm is both a part of the pose and places his right hand on his back where it frames the exit wound, reflected in the mirror.

SP 335. “Cicatrices After Shot Perforation of the Abdomen.” (CC-BY) National Museum of Health & Medicine.

A lot of photos from the early days of medical photography are posed as typical contemporary portraits. Although the wound is small, the pictures are full-figure and include one or more posing devices, such as a table and posing chair. In the photo of Barnum, the mirror is quite large and the reflection only fills half of the frame. In the photo above, a smaller mirror is placed discreetly behind the chair. Only the part of the mirror needed to see the reflection is visible. At first glance it may even look like a normal portrait.

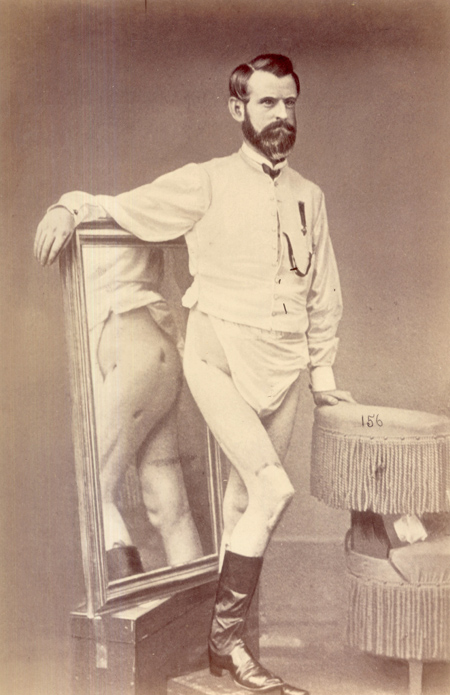

SP 156. “Recovery Without an Operation, After a Gunshot Fracture Involving the Right Acetabulum and Head of the Femur. 5 May 1862.” (CC-BY) National Museum of Health & Medicine.

Here is a shot where the mirror itself is used as posing device. As this patient had to remove his trousers to expose the wounds, the portrait style leaves this photo more comic than dignified. At least to today’s viewer. But it shows great creativeness in mirror placement. The nature of the injury demands that the patient must be standing, and instead of putting the mirror against a wall, or the posing chair, the patient supports the mirror himself. The shirt is used to hide the patient’s private parts is in many of these photos, but as we shall see, not all of them.

SP 0194. “Great Shortening of the Left Thigh, the Result of Comminuted Fracture of the Upper Third of the Femur By a Conoidal Musket Ball, with Removal of Fragment of Bone.” (CC-BY) National Museum of Health & Medicine.

It looks like the photographer pulled out all the props in his studio for this one, but it’s also packed with information about the patient. The ornate mirror shows a side view of the patient left thigh. The wrapped box on the floor clearly shows the shortening of the leg. And placed on the posing table, the patient’s specially fitted shoe. The large chair adds to the crowded feeling of the photo, but must have been the only item found to support the large mirror.

The shirt is not pulled down, but a fig leaf is covering his private parts. A quick look in the mirror however, reveals that it has been added after the photo was taken. It was actually painted on the negative for the 1876 Centennial Exposition, where a number of civil war photos where on display. This was most likely done to avoid offending the audience. Had it been done for patient privacy reasons, you would assume it would be more important to hide his identity than his genitals.

SP 166. “Case of Recovery After A Penetrating Shot Wound of the Ascending Colon. 17 Sep 1862.” (CC-BY) National Museum of Health & Medicine.

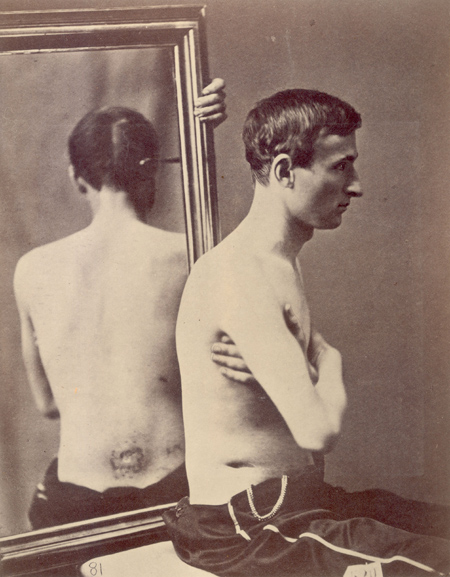

A few photos look less like elaborate portraits and more like modern clinical photos. The photos are half- rather than full-figure. The posing props have been changed for a simple stool which is only just visible in the frame and doesn’t draw any attention to itself. A very large mirror is used, which makes it possible to show only on side of the frame in the photo. This makes the mirror too, less conspicuous. The patient still turns his head as he would in a portrait, though. I think this is an injury where the use of the mirror is especially effective. Looking at the two wounds I find it easy to visualize the trajectory of the bullet.

SP 081. “Recovery After a Perforating Gunshot Wound of the Abdomen Producing Artificial Anus.” (CC-BY) National Museum of Health & Medicine.

Same kind of photo with two significant differences. Firstly, the patient is not looking at the camera but straight ahead and his arms are folded on his chest to keep them away from the entry wound. Looking straight ahead makes the face less important and placing the arms like this is nothing like a portrait pose. The photographer has instead placed the patient in a pose that most effectively reveals his injury. The second difference however, somewhat ruins this. Someone is holding the mirror and we see this person’s left hand. These out-of-place fingers demands all the viewer’s attention and leaves the patient less important.

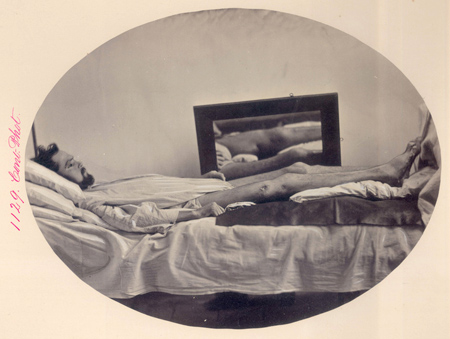

We’ll finish with two photos that represent problems involved in using a mirror. This first one is easily recognizable as a clinical photo because the patient is in bed in a hospital-like setting. But the reflection in the mirror is confusing. At first glance it may look like the soldier has been shot in both thighs, the mirror showing the reflection of the outside of the left thigh. This is not the case. It’s hard to tell from the photo, but the mirror is in fact tilted down towards the patient and is showing the exit wound on the inside of his right thigh. When you realize this it’s not hard to see, but when it is not immediately clear what the mirror shows, it is possible to misunderstand it.

SP 090. “Gunshot Fracture of the Shaft of the Right Femur, United with Great Shortening and Deformity.” (CC-BY) National Museum of Health & Medicine.

I am left wondering about this one (without a fig leaf, by the way). It’s a good anterior view of the soldier’s deformities, but his crutch blocks the reflection of the posterior view. In this case the mirror is useless. Perhaps the photographer didn’t see this, or maybe he had placed the guy just right but he lost his balance and had to move the crutch? Another problem is that the mirror reflects not only the patient, but also the other side of the room. This is distracting and would have been so even if the crutch was placed right.

Prisoner portrait with mirror, 1890s. Photo: The National Museum of Justice, Norway.

In the 1890s it was common in several European countries to use a special “shoulder mirror” for prisoner portraits. This was later abandoned for the more standardized double portrait (mug shot) still common today. This was seen as more accurate than the mirror portrait, as the size and angle of the reflection will vary with the placement of the mirror.

This is perhaps also one reason that the use of a mirrors in clinical photographs fell out of style some time around the turn of the century. After discovering these photos I am constantly looking for an opportunity to try the technique myself. So far no suitable patients or conditions have materialized. Too few through-and-through gunshot wounds, I guess.

Thanks again to Mike Rhode and the other kind people at the National Museum of Health & Medicine. Check out their blog A Repository for Bottled Monsters. All the Otis Archives photos featuring mirrors can be found here.

If you have seen other photos featuring a mirror in a similar way, please leave a comment.

Sources:

- Kathy Jane McFall: A Critical Account of the History of Medical Photography in the United Kingdom.

- J.T.H. Connor and Michael G. Rhode: Shooting Soldiers – Civil War Medical Images,Memory, and Identity in America.

- Stanley B. Burns – A Morning’s Work – Medical Photographs from The Burns Archive & Collection 1843-1939.

- Aud Sissel Hoel – Maktens Bilder (in Norwegian).

2016 update: I have published a sceintific paper on this subject called Mirrors in Early Clinical Photography (1862-1882): A Descriptive Study.

[…] Sterile Eye: Mirror of the Body. Medical photography of the past, with mirrors. Possibly […]

[…] in the US, and the Sterile Eye blog has a macabre, but fascinating, post on the use of mirrors in 19th century clinical photographs. Examples include photos of soldiers […]

[…] by the viewer of the photograph. (For some interesting observations on the Mirrors set, check out this post from The Sterile Eye, a blog dedicated to medical […]

[…] year back I wrote a post on the use of mirrors in vintage medical photos, with most examples from the American Civil War. […]

[…] see 51 of the photographs on the MET website here, and 6 medical photographs here. Also check out my post on the use of mirrors in civil war medical […]